Can you tell us what photos you plan to discuss in your lecture for The Democratic Lens on November 20?

I’ve been working in recent years on two long projects on family photographs, and families and photographs. Within that arena, I’m interested in the ways that imagining family life helps restore the nation after the Civil War .

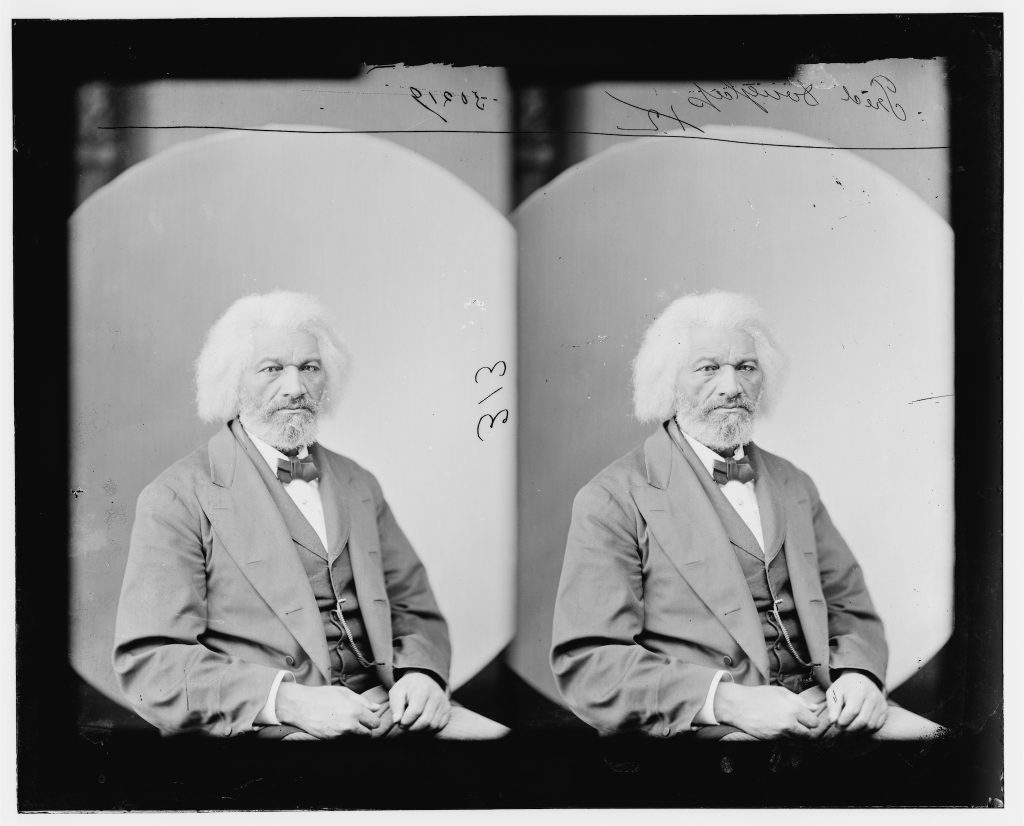

So I think I will begin by showing some of the many portraits Frederick Douglass had made of himself throughout his long career, and discuss his thinking about what photography could be, for his family, his people, and his country. His was a visionary idea of photography, in terms of imagining what it would mean to be American after the Civil War. He thought photography would be at the core of democratic practice after the Civil War.

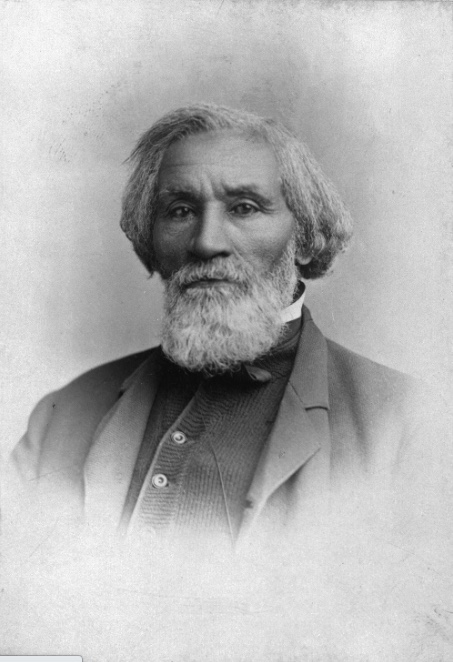

To clarify what he meant, I might perhaps also show some of the “Colored Conventions” digital humanities project [coloredconventions.org]. From the 1830s to the 1890s, African Americans were traveling around the country and meeting at conventions, debating politics and what role they would play in the country. For 70 years, there was this passionate tradition of political debate among African Americans, but we weren’t taught about that. The documents and images of these conventions and conventions were not collected in one place until this digital humanities project showed them to us. How did Douglass’ idea of political photography relate to this organized political practice? And where does domestic photography fit in?

In relation to Douglass, and our image of the Colored Conventions, I’ve also been interested in the photographic practice of his enemies—the redeemers who promulgated the violence of the Reconstruction period and Jim Crow. After the Civil War, the problem remained for the Union of how to re-legitimate the people who had rebelled against the U.S. government. Lincoln wanted to make it easy for the people formerly in the Confederate government and army to be reabsorbed into the nation. They were only required to swear fealty to the U.S. Constitution to get their U.S. citizenship back. By 1870, all the former Confederate states had been readmitted to the Union. But at the same time, many of the former Confederates themselves did not really relinquish their Confederate identity; they re-purposed it as the Lost Cause. We know, for instance, that these whites attacked Black legislators through racist caricature, while promulgating images of themselves as the true contemporary statesmen. But we know less about their simultaneous use of images of themselves as family men, even while we know that among them were the criminals and murderers of the lynching decades.

Henry O. Wagoner, who represented Chicago at the 1853 national Colored Convention in Rochester, New York, and served as secretary at the October 1853 Illinois convention. From ColoredConventions.org. (Source: Henry O. Wagoner, 1870-1890. History Colorado. Object ID 89.451.3861, CHS Scan #10026946.)

There’s the idea that Douglas had: that the country goes forward politically through photography. And there’s the idea that white supremacists had: that history goes back to what they wanted it to be—or as they would say, goes forward in a better way—through photographic images. I’m interested in the concept of restitution, in both the positive way that photographs enhance restitution, and then in the many ways that they are what I’ve started to call “social theft.” And I am asking, how do images of domesticity work to avert the gaze?

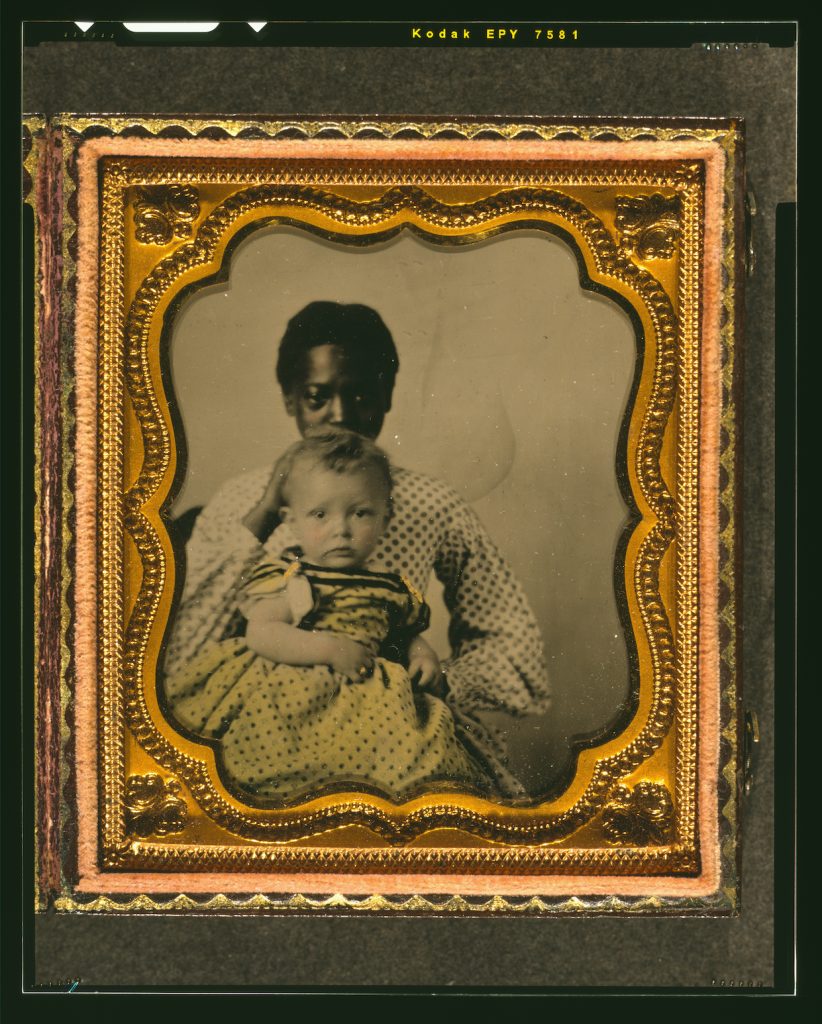

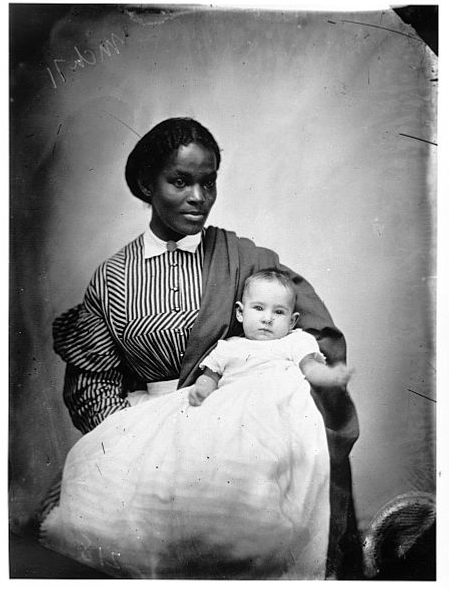

Speaking of images of domestic life, in your book, Tender Violence, you analyze some photographs that echo iconic depictions of the Madonna and the infant Jesus: startling images from the Civil War and Reconstruction of Black nursemaids with white babies they care for, and Gertrude Kasebier’s images such as “Ideal Motherhood,” made in 1899. Can you explain the context of these images of women?

Nursemaid photos are a genre in many parts of the world. When I was writing that part of the book, a friend in my writing group who was born in India was surprised that I was surprised: Of course!, she said. There are all these photos by the British in India of the ayah, the Indian caretaker of their babies. I learned it’s something that colonizers did around the world: Hired local women of color as wet nurses and nannies for their white babies, and took photographs of them. The two kinds of employment also blend into one another.

First, there’s a complete disregard of the wet nurse’s own family. To be lactating means they have their own baby somewhere. But if you are a wet nurse, you’re not feeding your own baby, you’re feeding someone else’s baby. Your employers may be taking sentimental photographs of you as if you are a member of their family, but they’re not taking photographs of you with your own baby.

Later, those kinds of photographs are also very much involved in the production of the idea of the nursemaid, or mammy, as a loyal servant who is perfectly happy to work for you. Her milk, her ability to nourish, her story, and her image all belong to you. Historian Thavolia Glymph has done brilliant work reconstructing many white women’s alarm, expressed in their letters and diaries during and after the Civil War, when they found out this was not so, alongside many Black women’s determination to reclaim their own representation.

Nursemaid photographs offer a good example of social theft: What are we seeing and what are we not seeing in a given picture? For every image offered, others are taken away. There’s a quote from Roland Barthes that I love. In Camera Lucida, he says: Photography is violent because it fills the eye by force. What he means is that the all-at-once-ness of an image convinces you that what you’re seeing is what you are looking at. But this may not be true. A photograph doesn’t get created all at once; it is forged from layers of meaning, cooperation and coercion of those involved. Things may be deliberately excluded. The image hits your eye all at once, but only slowing down and processing the layers of meaning in that all-at-once-ness enables us to think about photographs rather than merely be affected by them.

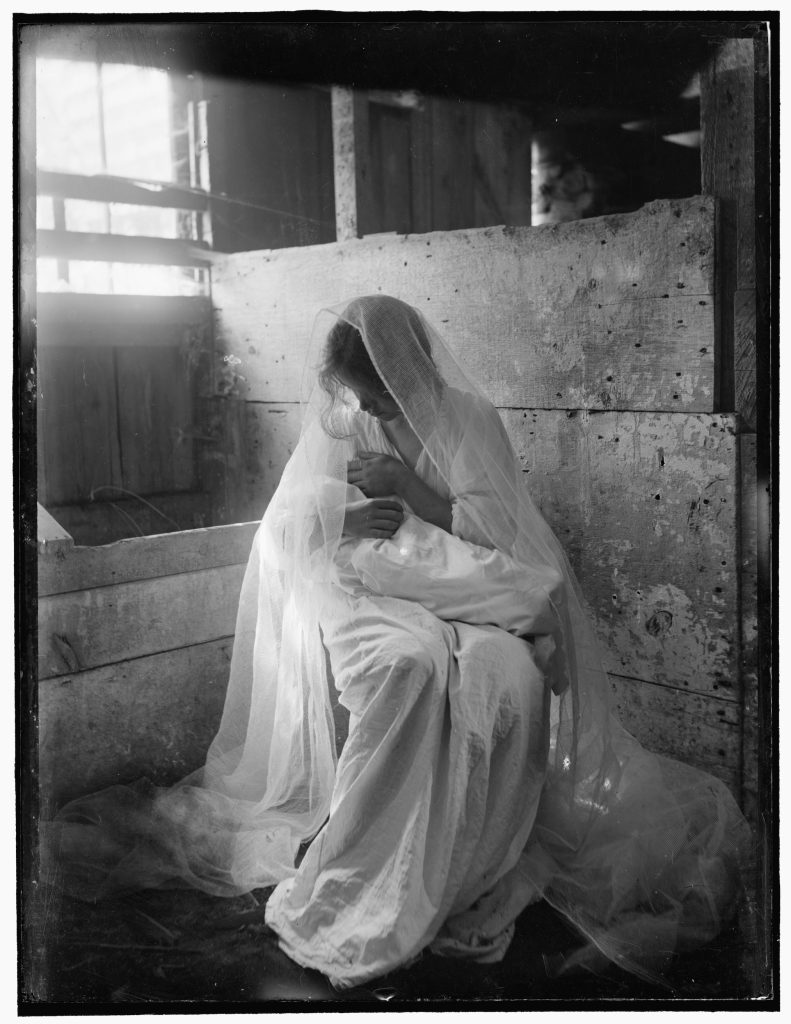

What was happening when Gertrude Kasebier made her sentimental images of motherhood?

Kasebier is working in the Progressive period when Teddy Roosevelt is worried that white women—he means middle and upper class white women— are not reproducing, and Madison Grant is writing his eugenic tract, The Passing of the Great Race. They are encouraging motherhood as an ambition and trying to discourage all these women who are having careers without also having families. It’s the same period that sees the largest influx of southern and eastern Europeans to the U.S. and the greatest wave of immigration to the country until now. The white elite is worried about losing control. Kasebier’s images reflect the world she knows. There is often a critique of the saccharine tone of this celebration of mothers, since she knows that there is often pain and tragedy, too. She also turns away from the constriction of her own domestic life to become a portrait photographer. But she does not venture further. What’s unfortunate is that in her own self-assertion, she is not also celebrating other people’s motherhood. I don’t have any problem celebrating motherhood, but let’s celebrate everyone. Nearly every one of Kasebier’s pictures is saying this white motherhood is the pinnacle. We’re basically not seeing the aspirations of Native American motherhood or African American motherhood When coupled with U.S. imperialism abroad and Jim Crow at home, this becomes a dangerous proposition. I call it social theft.

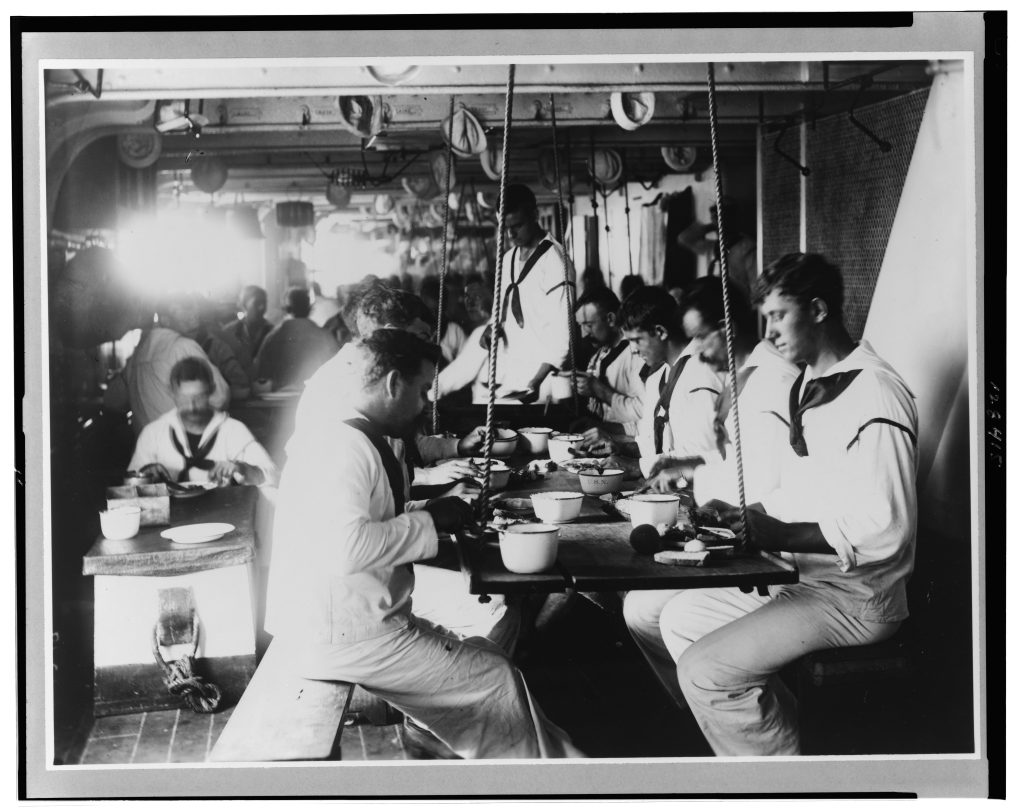

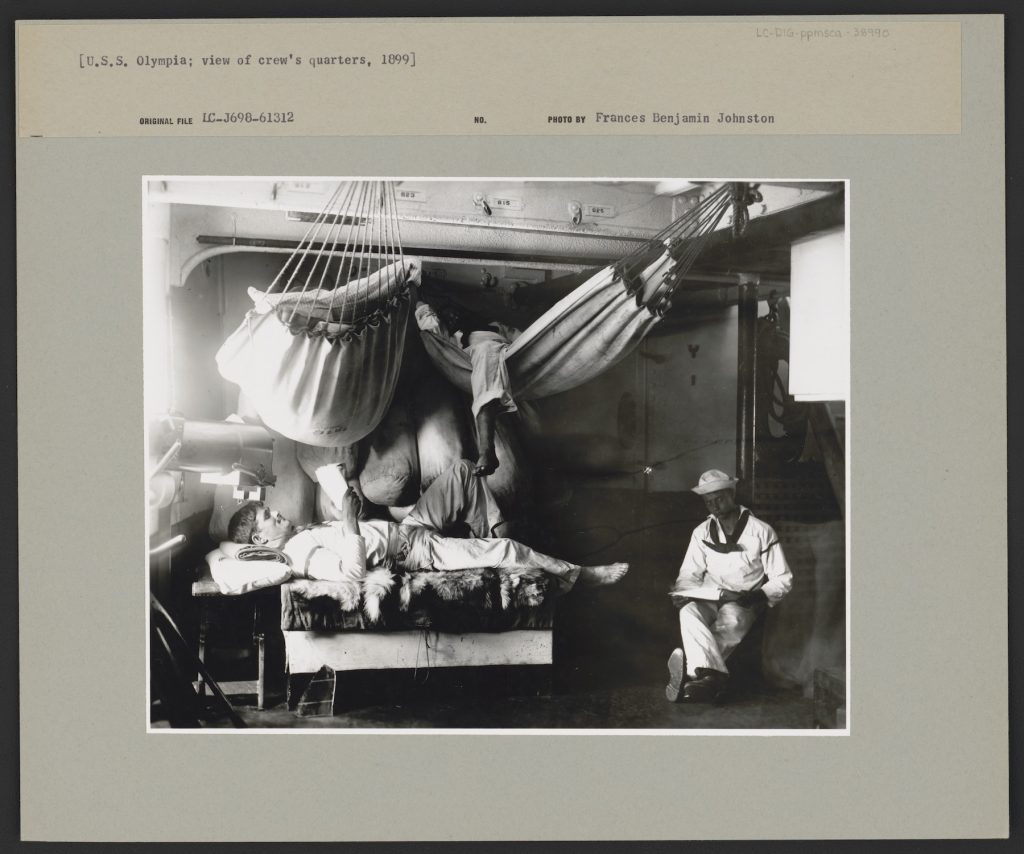

In Tender Violence, you write about the first generation of white, middle class women professional photographers as prototype photojournalists. They gained “unprecedented opportunities for a public voice in turn-of-the-century America” with images that enhanced America’s imperial ambitions and white male culture. One of the ways they did this was through what you have called “the averted gaze.” Can you give an example, and explain what the photographs ignore?

I think a clear example of this would be Frances Benjamin Johnston photographing the young crew aboard Admiral Dewey’s ship returning from the Philippines. What the images remind me of are pictures Johnston made of her social group of artsy friends in DC. society, an image of domestic life. These charming, young, handsome soldiers are the same ones who have been burning villages and women and children and inventing waterboarding torture. How can these young American boys, who are going to be war heroes when they get home, be the same ones who torture people in the Philippines? We’re led by her looking to see one thing, and at the same time it turns our eyes away from the other. Like the nursemaid photographs, I think, the averted gaze here is also about that shift.

Johnston was among the extraordinary group of white women who, in the last decade of the nineteenth century and the first decade of the twentieth, pioneered photojournalism. A lot of them started —like Kasebier— by running their own portrait studios, but then they moved out of those studios to photograph the broader world. They were starting to build their own capacity by realizing there were opportunities, first beyond, say, teaching, nursing, and mothering, and then beyond the studio. Johnston, for instance, first set up a studio in Washington and took commissions photographing her circle of bohemians, but she also started branching out photograph in in a coal mine in Pennsylvania, for example. Jessie Tarbox Beals, for another, taught for a while and after doing some freelance work, realized she could make more money as a photographer than she could as a schoolteacher.

But simultaneously, perhaps unknowingly or perhaps not, these New Women also became important projections of United States imperial power. I’m not saying the women aren’t doing amazing things, but they’re being used by the patriarchy without acknowledging it. One way we project our power that is we make it safe for American women to be abroad. The American woman needs to be protected, so if she can be out there far from home, and she is still safe, that’s because we can keep her safe. Her safety is a symbol of our power. Our women are strong and free, yours are not. Our women are evolved, yours are behind.

During the war in the Philippines, there was a commonly expressed idea that the U.S. was the benevolent big brother to all the “little brown people” in the islands, committed to teaching what true civilization was. To put it acerbically, the story of civilization turned out to be the one in which the United States has to conquer Philippines directly after they had won their independence from Spain. Who better to make images of this story than a strong free American woman like Frances Benjamin Johnston?

In the book, you also suggest that once American hegemony and the anti-immigration agenda are realized, the images by Johnston, Kasebier, and Beals are no longer needed or celebrated.

Not only their images. Their public presence also contracts. Johnston, who reinvented herself numerous times, and so had a very long career, is an exception to this rule. What interests me is the continuing instrumentalization of American women’s capacity. That’s what I saw around the imperial wars of the late 19th century, and I saw it again while I was writing the book, during the first U.S. war in Iraq.

I’m interested to see if it is also going to happen with the war in Ukraine. I’m curious whether this structure-- the instrumentalization of American women photojournalists in the field as a projection of U.S. power—will still hold, given all the changes in media. I recently read that there’s a documentary being made about Lynsey Addario’s work in Ukraine. But I don’t see that being done for local photographers, who have commented on the film crew and the security people who accompany her. It makes me wonder: What is the purpose of that documentary? Obviously, it is interesting to see her work, which is extraordinary. But what else are we also being shown?

In Pregnant Pictures, co-authored by you and Sandra Matthews, you look at 20th century images of pregnancy. How did advancements in fetal imaging and photos of embryos, without showing a woman’s body, influence public policy? What prompted you to write the book?

I’m sure you know that Bernard Nathanson and the Right to Life people early on made a very powerful video, The Silent Scream, that falsely animated Lennart Nielson- type images of a fetus to make it look like a child sucking its thumb, and crying out in pain in the process of being aborted. Since the Dobbs decision, Sandra and I have considered doing something more with this work, because the politics around images of the fetus and” fetal personhood” have gotten even more drastic.

This politics is built on the erasure of the woman except in so far as she is ground for this fetus. I experienced this erasure myself. I was in maybe the third year of women faculty hired at Amherst College after it went co-ed, and I became pregnant. Sandra Matthews was at Hampshire College in a similar situation. The experience we had was brutal. I experienced hostility, that what I was doing was unacceptable, to think that I could have a baby and teach at the same time in a place like that. We also couldn’t see ourselves—working and pregnant—reflected in images that might have countered this negativity. There was no maternity leave. There were pictures of childbirth and pictures of the fetus, but the woman, who has continually to make decisions about her pregnancy and tries to make a concerted effort to maintain and optimize it—we didn’t see reflections of this woman’s experience. It was not benign.

We did lots of research in medical libraries. We looked at ads for maternity clothes, which were fascinating. We put notices in clinics and people from all over the country sent us their own snapshots which I found fascinating. They were so unconstrained compared to the modernist photographers who have codes about how to show what pregnancy is: they often put the pregnant woman next to a potted plant, for example, equating the woman with nature as the container where the seed is grown.

Pregnancy was also changing in that time: in vitro fertilization, Louise Brown, the first test-tube baby, even the intimation of transgender pregnancy. That change was not reflected in the canon of images.

We wanted to say: Pregnancy is a real thing, an effort in people’s lives. It’s not something that just “happens” to them and then requires no further attention. To see that, you have to look in a way that’s more pointed, expansive and creative than most of the images we found, except for the wonderful vernacular snapshots that people sent.

Reading Pregnant Pictures, I was struck by the class differences between the pregnant women shown artfully in the studio or imagined spaces, and the pregnant women shown out in the world in documentary images that suggest their pregnancy is problematic. You’ve also discussed images of pregnancy and motherhood that appeared at times of certain anxieties—about the birth rate among whites, or about government assistance for poor women having children. Can you talk about some examples of images that address these anxieties?

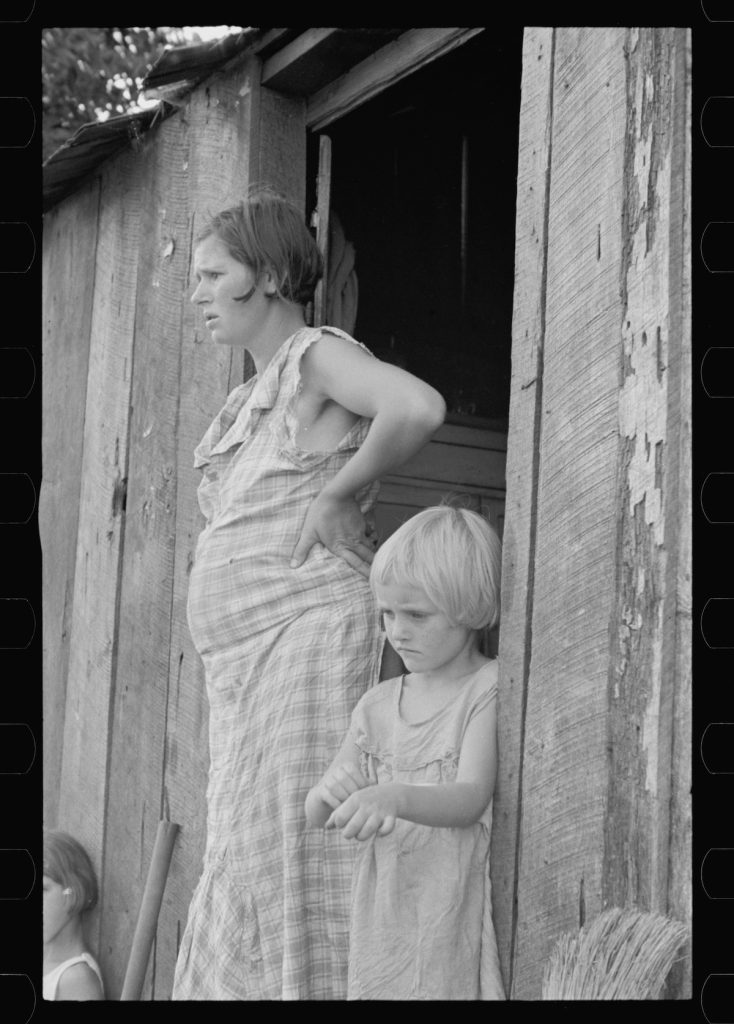

One example that comes to mind is that during the Depression, for the Farm Security Administration, it could be politically toxic to photograph poor migrant women with lots of children to show that they were in need of support because a lot of the country didn’t want to pay taxes to support them. This was a difficult problem for Roy Stryker, who was trying to help the government build resettlement camps. When, early on, the FSA had a big public exhibit in Grand Central Palace in New York City, they let people write responses to the exhibit, and someone wrote, “Teach the poor to have fewer children and they will have less struggle supporting themselves.” In Dorothea Lange’s photo of Florence Owens Thompson, the iconic image of “Migrant Mother,” not all her children are visible. That mother has more children than what the iconic photo shows. Who gets to be the sainted mother in a Kasebier image? In a Lange image? What are the pressures that avert the gaze, building on erasure like the nursemaid images?

As filmmaker Dyanna Taylor, Dorothea Lange’s granddaughter, discussed with me, Lange often photographed Black farmers and sharecroppers in the South, but Stryker didn’t release the images as part of the FSA’s publicity efforts.

She is absolutely correct. At every moment, Franklin Roosevelt’s program was under attack, particularly from southern Senators. Stryker even smuggled images out of Washington to the New York Public Library, after the FSA was ended, like people saving climate change data after Trump was elected. The hostility to the work was enormous.

They’re heroes of mine. But we have to understand the pressures they were under. To understand what we’re seeing, we have to understand that our gaze has been averted by those pressures. I’ve called what I study “the social life of photographs.” It includes the notion that photographs aim to either stir up or redress specific anxieties. Why does anyone pick up a camera? There are questions, and the camera seems to be an approach to answering those questions.

REFERENCES & RELATED READINGS:

• Image Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California. 1936, often known as “Migrant Mother” © Dorothea Lange, for the U.S. Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information. Provided by the Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division. https://guides.loc.gov/migrant-mother

• Johnson (Frances Benjamin) Collection, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/fbj

• Laura Wexler, Tender Violence: Domestic Visions in an Age of U.S. Imperialism, (University of North Carolina Press, 2000). https://uncpress.org/book/9780807848838/tender-violence/

• Sandra Matthews and Laura Wexler, Pregnant Pictures, (Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2000) https://www.routledge.com/Pregnant-Pictures/Matthews-Wexler/p/book/9780415921206

• The Cook Photograph Collection, Virginia Commonwealth University Digital Collections. https://digital.library.vcu.edu/islandora/object/vcu%3Acook

• The Silent Scream. Directed by Jack Dabner, with Dr. Bernard Nathanson, American Portrait Films, 1984. https://www.routledge.com/Pregnant-Pictures/Matthews-Wexler/p/book/9780415921206

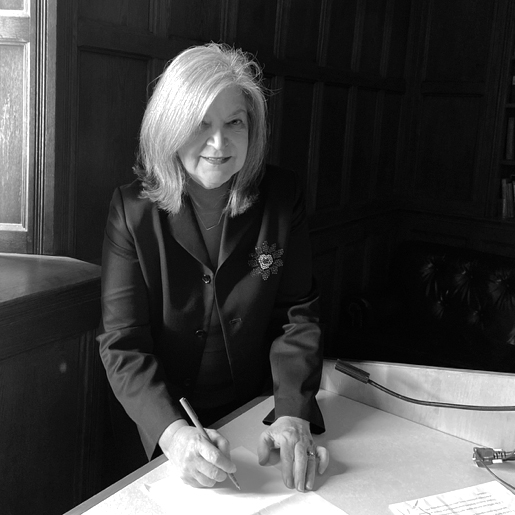

This interview was conducted by Holly Stuart Hughes, Independent Editor, Writer & Grant Consultant, Former Editor-in-Chief, PDN, in October 2022.