In your public lecture on November 20, you plan to talk about “empathy as a perspective.” Can you tell us some of the images you plan to discuss, and what got you thinking about “empathy” in images of war.

Let me walk you through the lecture. I’m a curator so I start with the photos, and learn from the photographs and the photographers.

I’m probably going to begin with definitions of empathy. These come from many sources, but Hilary Roberts of the Imperial War Museum in London, my go-to authority, has sent me several articles and books. From everything I’ve read, empathy is about forging a connection with another person that enables understanding. Cognitive empathy is the ability to understand another person's point of view. Emotional empathy is the ability to understand a person's emotions. Somatic empathy is the ability to feel another person's physical sensations. I’m curious whether that includes the experience of physical pain. Historical empathy is the ability to contextualize events from the point of view of someone who experienced it firsthand.

With co-curators Will Michels and Natalie Zelt, I worked on the War/Photography show for eight years. We started knowing nothing, but we traveled widely around the world and around the US, and we met a lot of people who were in the military or had previously served in the military as well as photojournalists who had covered armed conflict. The consensus was that you can't understand until you been in a conflict or at least in training. War is its own world. Historical empathy, an understanding of what happened and its impact on you, is something I’ll talk a lot about when I get to the stage of the lecture that involves showing what people have been through.

My final comment is: Empathy is not sympathy. It is not compassion, or “I'm sorry this happened to you,” or a pat on the back.

When the War/Photography show was up, we had therapists on call, in case the museum guards saw someone in emotional distress, because the exhibitions triggered experiences. We once saw an elderly man, sitting at the end of the exhibition. That’s where we had cards that people could post on the wall with their comments about the exhibition. This elderly World War II veteran said, “It’s a powerful exhibition, but you've left out something really critical.” I asked him what, and he said, “Smell. The smell of bodies, the smell of dead animals, the smell of ammunition.”

I’m going to show some photos of wartime cruelty shocking in its magnitude. There’s a Ron Haviv photo of a Serbian soldier with a cigarette in one hand kicking elderly people he has just shot. Next we have a photo of a soldier watching President George Bush apologize for the abuses at Abu Ghraib prison. I’m trying to get from a friend in Ukraine images of the decimation of homes and civilian deaths by Russian missiles.

I’ll include a photograph by Jonathan Torgovnik of a Rwandan woman with two children, one of whom was borne of her rape during the Rwandan genocide.

So you’ll be looking at images that evoke empathy both for combatants and for civilians. This seems to be an aspect of many photojournalists’ work in the 20th and 21st century that wasn’t common earlier, in images made, for example, during the U.S. Civil War.

You cannot separate civilians from war now. Go back to photographs of World War II and images of the bombing of Dresden.

I’ll also look at an aspect of death, of soldiers comforting or cradling a dead or injured comrade. We have the Larry Burrows photo from the Vietnam War of a bandaged soldier reaching out to his wounded comrade on the ground. There is a photo from the Korean War by Al Chang, and one of the things that is so powerful is that there’s a man cradling his friend while next to him a man is methodically making lists of dog tags of killed soldiers.

I’ll also show some powerful series by Todd Heisler and Ashley Gilbertson. Todd Heisler in “Final Salute” shows a casket being unloaded from a plane as passengers’ faces are seen in the windows. Then he Later Marine Major Steve Beck brings in the family, to view the casket. The image that gets me every time is that the widow wanted to sleep beside her husband's coffin. And she asked the Marines to stand guard, and they stood there all night in uniform.

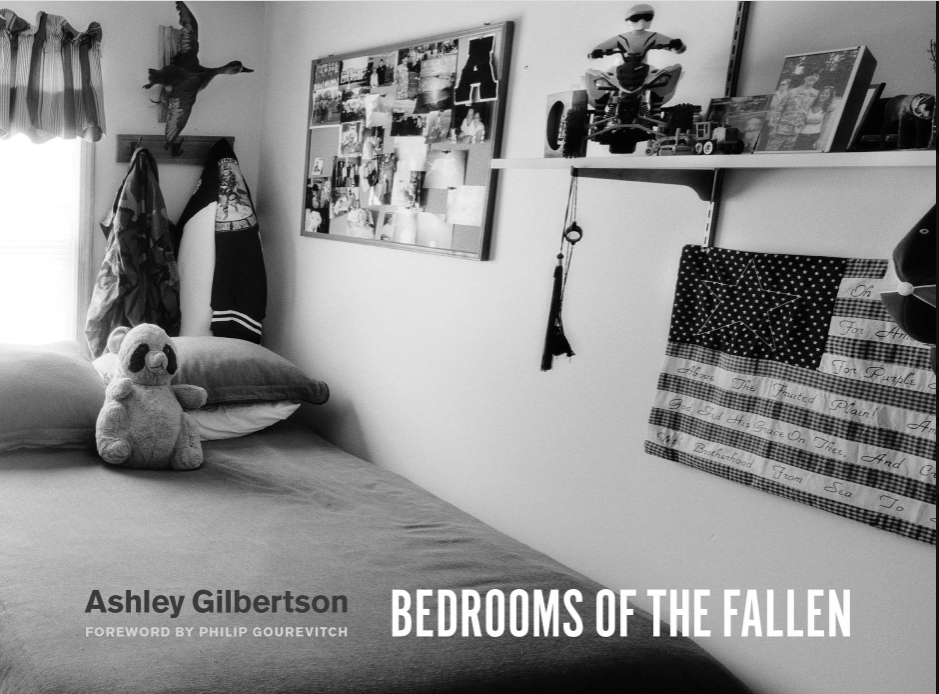

Ashley Gilbertson felt that a lot of war images had fallen into certain tropes, and he was looking for something different. He made “Bedrooms of the Fallen,” showing the bedrooms of fallen soldiers that their families left intact. Gilbertson believes that we have become immune to heroic photos of war and its aftermath. He wanted to find a different perspective that would make people feel some empathy.

I think for a lot of the public, these pictures not only will be fresh but they'll be literally closer to home. They’ll be hit by what the families were trying to hold onto.

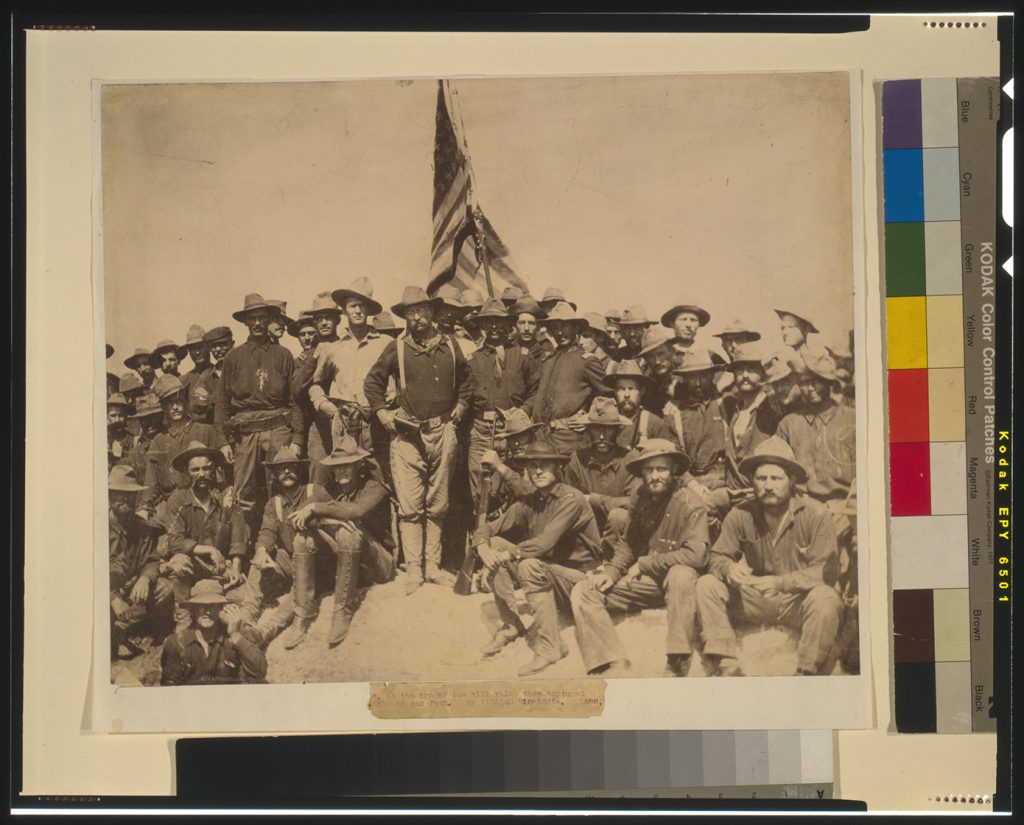

I’m struck that you are showing images empathetic towards soldiers’ suffering. The majority of war photography, from the earliest war photos made during the Mexican American war, have been either posed portraits of soldiers, or they celebrated soldiers running towards action or as victors after battle.

The portrait of Teddy Roosevelt and the Rough Riders after taking San Juan Hill in Cuba in 1898 was very influential in his political career. It led to him being president. It’s all about heroic flag-waving. What’s also interesting about that photo is its ethnic diversity, at a time when the U.S. military was not diverse.

For the section of War/Photography on recruitment and training, we saw many photos that were very rah-rah. They showed young men who had no idea what they were getting into. There’s also the fact that many veterans never discuss their wartime experience. The heartbreaking part is coming home with what we call Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder or shell-shock, and the shame and mental disturbance that surrounds it.

I also have photos showing moments when photographers stopped what they were doing and became involved. Nick Ut not only photographed Phan Thi Kim Phúc, the running “Napalm Girl,” but he and others took her to the hospital, and she and Nick developed a lifelong relationship.

There was a photograph made in Fallujah in 2004, in the most horrific, lengthy battle of the Iraq war. Luis Sinco of the Los Angeles Times took a photo of Marine Lance Corporal James Black Miller where his face is full of mud and blood and he’s smoking. It was dubbed “the Marlboro Man” and immediately published in 150 US newspapers. The Marines wanted to send Miller home but he decided to stay. “After a while, he said, you’re fighting for your buddies, and I couldn’t bear the idea of getting to go home and leave my buddies.” He stayed for his tour; when he got home he had really bad PTSD. Luis Sinco stayed in touch and finally said Miller, “That day in Fallujah, if I had been injured would you have carried me out?” and he said of course. Luis said, “You have to go into therapy. I’m carrying you out.” Cinco continued to visit with him.

That kind of trust can only occur when the photographer has been there, and been beside them. There’s that feeling one has about the people you’ve gone through an experience with.

What you’re describing are images of intimacy between photographer and individual service men and women. Was that intimacy possible before photographers could work with lightweight 35 mm film cameras, rather than the heavy cameras used to make, say, glass plates?

That starts before World War II with the Leica camera. The fluidity the photographer who captures a moment of action with a 35 mm, like the Robert Capa photo of the moment of death of the soldier during the Spanish Civil War, you can’t do that carrying a tripod.

Something that’s not engaged here is drone warfare. The person manipulating the drone miles away may never see what happens. They have only coordinates.

Empathy is possible when there’s a connection person to person. The seed of my wanting audiences to think about empathy is the incredible hostility commonly expressed in this country.

REFERENCES & RELATED READINGS:

• Anne Wilkes Tucker, Will Michels, and Natalie Zelt, War/Photography: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath (Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2012). https://www.amazon.com/War-Photography-Conflict-Aftermath-Houston/dp/0300177380

• WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath, 11 Nov. 2012 - 3 Feb. 2013, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas. https://www.mfah.org/press/warphotography-photographs-armed-conflict-and-its-aftermath

This interview was conducted by Holly Stuart Hughes, Independent Editor, Writer & Grant Consultant, Former Editor-in-Chief, PDN, in October 2022.