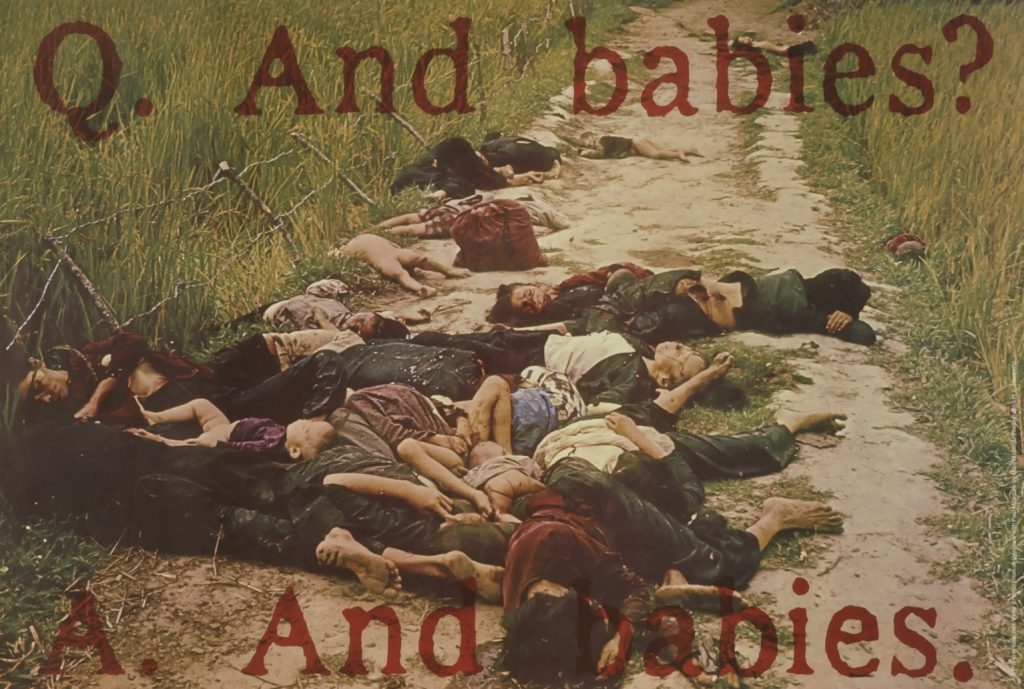

CONTENT WARNING: VIEWER DISCRETION ADVISED -

“In an era where the lens is mightier than the sword, activist photography emerges as a profound means of inciting societal transformation... In this light, activist photographers are akin to modern-day revolutionaries, wielding their cameras as instruments of social awakening.” 1

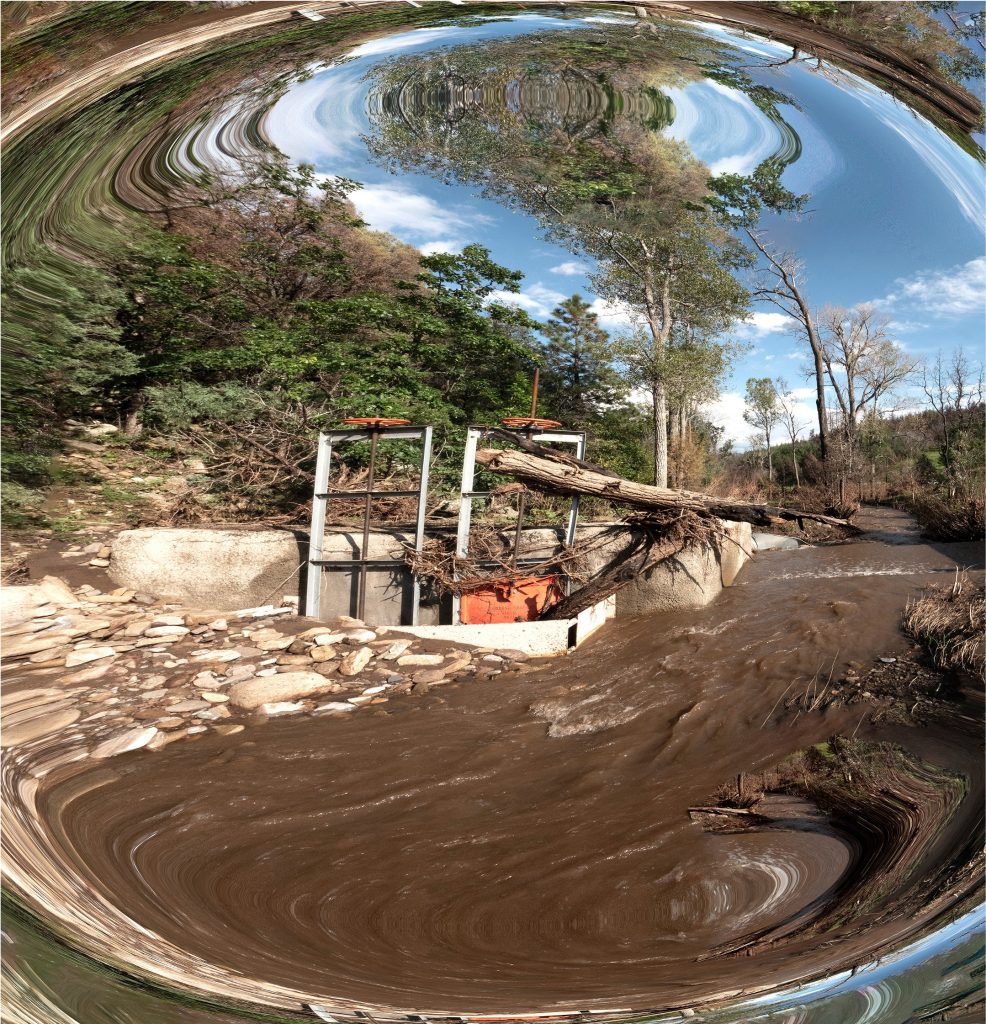

All the world’s an image, especially ever since photography became widely accessible, and then even more so since cell phones, the internet, digitization, and manipulations, which have made it possible for photographers to lie (or fictionalize) more easily. Yet photography continues to be believed more than “made up” visual art, despite the fact that it can no longer be confidently associated with recorded truth. One timely example: When Israeli leader Yitzak Rabin was assassinated as he left a peace rally in 1995, photography was an accessory to the crime. The Zionist right wing under Benjamin Netanyahu had long been plastering thousands of altered posters of Rabin in a traditional Palestinian keffiyah all over Israel. Photography plays a more instructional and revelatory role with images by Palestinian photographer Yasser Nassim emerging from occupied Gaza, where maimed and wounded patriots have for decades employed slingshots against Israeli snipers, tanks, and bombs. And of course personal cell-phone videos have proved even more powerful weapons against police violence and other criminal cases.

I define activism as actions and images hoping to change something.2 Photojournalists image events, actions, and crises for future dissemination, directly informing the public. It’s about taking risks and acting on beliefs and ethical imperatives as well as looking, thinking, supporting, and learning. Activist photography comes in many different flavors, some of which are called art. One iconic example is artist JR’s Eric Garner’s Eyes, his gaze amplified in huge images leading the Millions March NYC protest in 2014. On the Navajo Nation, Jetsonorama (Chip Thomas) an African American physician and artist, has worked in unexpected rural sites for decades. JR’s huge toddler peering over the U.S.-Mexico border wall is another impressive example.

Photographic time is expansive and deracinating, existing in the moment it was taken and then in the moments it’s perused. Different types or origins of images move different people, even different social sectors, at different times. Not to mention those deliberately employed and distorted for disinformation. And one has to wonder if a population addicted to social media can still tell the difference.